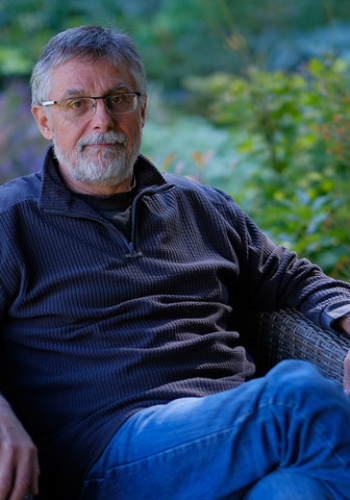

Mountaineer and former top manager Zoltán Demján says that the goal alone is not enough. Success in the mountains and in business depends on its proper formulation, on the ethics along the way to it, and on the deep sense of meaning that keeps people going in crises. Only the balance of these elements turns an ascent into a true return home.

A goal that ends only in the valley

“Reach the summit” is not a good goal, Demján argues. The right one is: climb as high as possible and return safely, because most tragedies happen on the descent. If the goal is poorly set, a person “charges ahead blindly,” exhausts their strength on the way up, and has no energy left to get back. This applies in the mountains and in companies: success is counted only with a safe finish, not at the first “checkmark.”

Your mental state plays a big role in achieving goals. Clear rules, a realistic pace, and conserving energy are just as important as performance. Demján reminds us that you should view the ascent as an entire cycle—from departure to return, not just the few famous meters below the summit.

Ethics on the rope: how we act matters just as much

Debates after the tragedy of a porter on K2 showed how hard the decisions at extreme altitudes can be. Demján emphasizes that exceptional situations exist, but in the vast majority of cases help is possible. An environment of respect and kindness frees people’s minds to solve problems, while pressure and stress block them. In the mountains and in teams, the culture of how we treat others is decisive.

He himself described how on Peak of Communism he descended with an exhausted mountain guide whose feet were getting frostbitten. He no longer thought about the summit—the more important thing was to get the man to safety. After a few hundred meters of vertical descent and with more oxygen, the man recovered and gratefully gave him a down jacket. This “missed” summit thus turned into a moral victory.

Meaning as fuel: from SAP to Everest

Demján’s management story with the implementation of SAP shows what happens when meaning is missing. The company wanted to be “first” and have “everything,” but without a clear why it used only a fraction of the possibilities and patched together broken processes. Only when they clarified that the goal was easier work, better service for customers, and only then savings, did things start to work. First you need meaning, then a goal, and finally the tools.

During the descent from Everest in a nighttime blizzard (around 130 km/h), his partner Juzek Psotka died; Demján survived only with difficulty. What kept him going was the thought of his family—a sense of meaning we feel not only in our head but also in our heart. Equally important is to know when to stop at your best: after years he left both extreme mountaineering and top management, and he warns against burnout, which today affects even people in their thirties. The balance between meaning (yin) and goals (yang), he says, is a simple yet powerful principle that helps make things work in life and in companies.